Foreword

Kahn revisited

Giuseppe Strappa

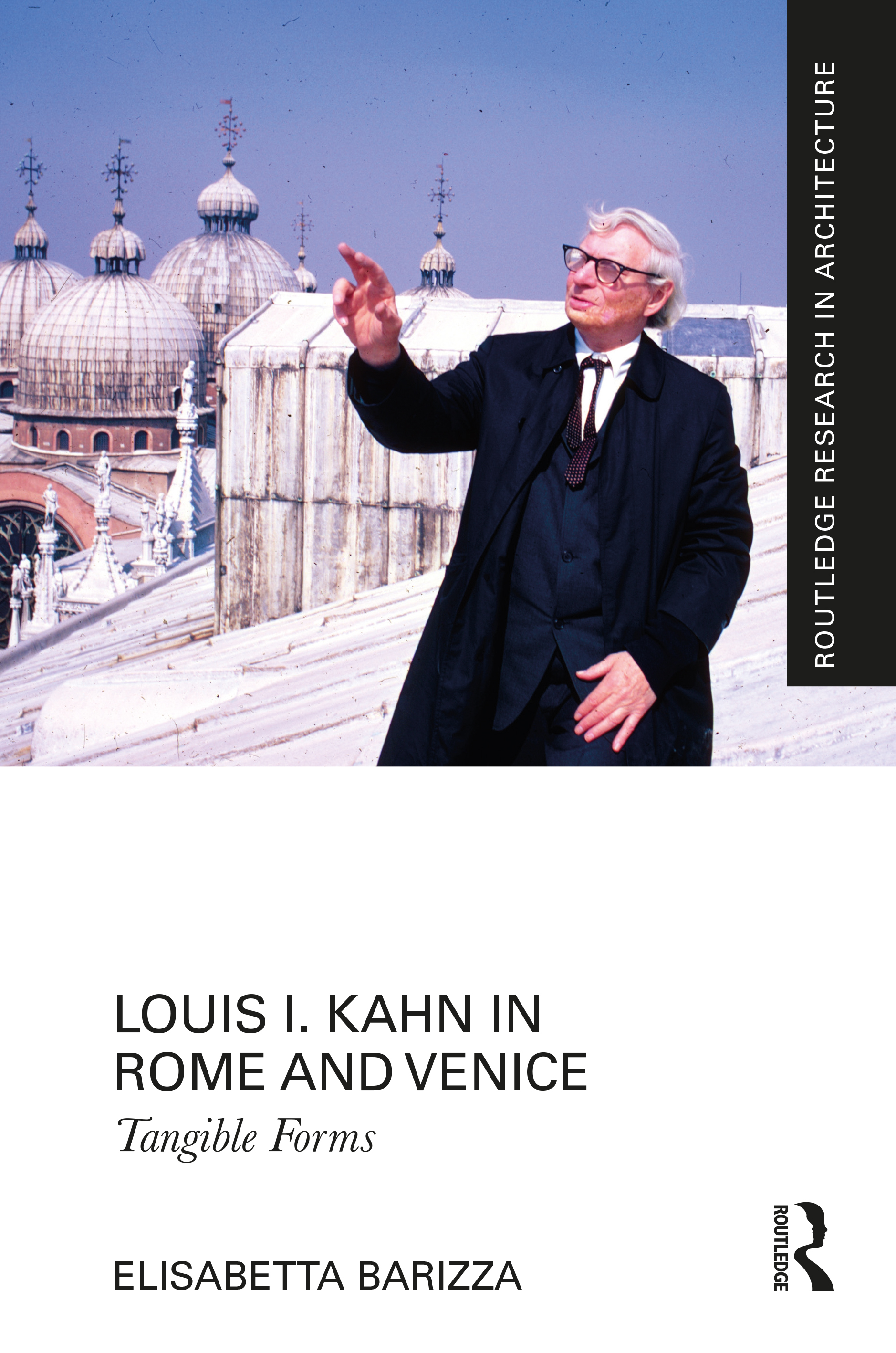

In architecture, certain ideas and key figures need to be continuously reinterpreted, and each generation has its own form of reinterpretation. It has happened in the past in the case of certain architects, from Vitruvius to Borromini, whose lessons in creativity end up being the product of the times in which the interpretation took place, a result of the many, changing readings that have been made, layer upon layer, over time. It happens still today. I believe, however, that this fruitful form of rethinking and further examination is readily, if not principally, applicable in the case of Louis Isadore Kahn, who was the bearer of a message that was, by its nature, predisposed, one could say, to many different interpretations.

This book – the progress of which I have had the pleasure of following during its various stages of evolution – proposes exactly this: a new interpretation of Kahn’s legacy carried out with scientific scrupulousness, while being aware of the critical state in which design projects find themselves today. A “new” Kahn, in other words. A Kahn, certainly, who is completely modern, since in him are embodied the anxieties and abuses of the contemporary condition. But his is a modernity that is exceptional and different, one to be totally re-examined, because he painfully attempted to diagnose these divisive factors and re-arrange them in a single framework, to recompose the scattered elements of the shattered reality around him into an ideal form that would unify everything and hold it in place. In this quest for knowledge lies all the drama of Louis Kahn, and his perpetual innovation: surrounded by the most contradictory of all possible environments – the America of mass-production industry and market forces – he imagined a different, organic world, in which each thing had its own place in accordance with timeless rules (timeless, not ancient), and where everything recomposed itself, in a way unlike what happened in the past, of course, since nothing can take place without change. In a world dominated by speed, Kahn managed to perceive, once again and afresh, the slow, eternal ebb and flow of life in architecture. This concept was not linear in time, one could say, but a kind of cyclic, endless reappearance of forms.

I believe it is important for us to recognise his ability to place a measure on things, to set a limit that determined the actual meaning of a form: progressively rediscovering the poetic wisdom of the rule, and how it had functioned so well throughout history. We can sift through the ruins of a major calamity, but Kahn seems to be telling us that we know how to put those ruins back together again, like the young man in Tarkovsky’s Andrej Rublev, who faced with the annihilation of every scrap of traditional knowledge, remembers how to cast an iron bell, and gives this information to his fellow-citizens who are wandering lost among the destruction wreaked by the invasion of barbarian hordes.

And so, this re-composition, this activity of reconstructing anew what has been broken and scattered, is the great epic theme of Kahn’s entire course of experimentation, the anti-modern “other side”, we might say, of some of his many contradictory facets, which does not allow for simplification. This idea was inherited, to a certain extent, from Paul Philippe Cret, a remarkable architect and educator, whose career has been somewhat overshadowed by Kahn’s bright shining star, but which has also been dignified, as Elisabetta Barizza points out, by a recognition of Cret’s fundamental maieutic role in Kahn’s education. However, I believe that in the American architectural milieu, Kahn’s message was fated to fall on deaf ears. Despite the formidable amount of work that went into spreading his views, and the efforts of art historians in exploring influences and interconnections, there are few traces, in the work of architects of his time or later, of the influence of Kahn’s passing star.

The power of his architecture has, on the other hand, been the unintended driving force for an entire generation of Italian architects, who themselves had been brought up on teachings that differed from those of Cret, yet which were, in some sense, linked to them by an underlying idea of unity between parts, conveyed by geometry. Above all, the semi-forgotten notion of organism, put forward by teachers in Italian architectural faculties (in particular, that of Rome in the pre-war years), acted as an underground stream, deep-running and subliminal. Perhaps for this reason, Kahn’s teachings held a particular attraction for some members of the architectural scene in the 1970s, when, during a period of crisis and impermanence, they seemed to offer the illusion of certainty and longevity. Kahn appeared above all to bestow a new sense of pride and faith in the ways and means of architecture, which, long under threat for its basic principles, at that time was reclaiming its independence as a discipline.

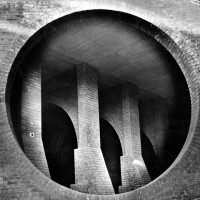

Yet there was another affinity that, to my mind, favoured Kahn’s reception in Italy: a distinctive, Mediterranean way of perceiving the tangible quality of materials. The plastic potential inherent in Kahn’s work was, to a large extent, due to the genuine, masonry-based solidity created between spaces and construction, between the walls that supported the weight of a building and, at the same time, closed up the spaces; it also relied upon the form constructed out of the organic act of holding all the component parts of a project together. An act that nonetheless abandoned the precision of classical measurement, the ideal home of all ideas of organism, and took into account the fact that the ancient geometries of perfect cosmogonies had given way to the ambivalences of the modern world, and it was no longer a question of maintaining absolute unities, which did not include at least the beneficial seeds of the undefined. Since our minds have need for a crystal-clear esprit de géometrie, our hearts welcome the devices that create large shadows, the mystery of collapsing spaces, the light that shines from some hidden source, the glare that we want to shield our eyes from. Courageously, Kahn once more brings forth forgotten, grandiose themes that appear to engage the central core of an architect’s work: great imposing public buildings, the malleable design of monuments and the study of Platonic forms created by a meta-historic line of reasoning far removed from any form of internationalist rationalism. Thus, Kahn, using a language that was immediately comprehensible to Italian architects, assuaged the widespread distress and discomfort that emerged at that time, as architects were confronted with a modernist legacy, the limitations of which were already seen to be too confining. His ideas soon uncovered the real nature of this cultural crossroads – a point where many came together, or found themselves, only to disperse once again and follow other paths. That however brief moment of meeting nevertheless appeared to lay down a lasting foundation for an identity that was otherwise on the way to extinction. What would the researches, albeit original, of Franco Purini, Alessandro Anselmi, Claudio D’Amato, Massimo Martini and many others (if we consider only the Roman architects) have been like, without their encounters with Louis Kahn? I think that even apparently distant cultural contexts, such as that of The Swiss Ticino canton, managed to forge historical links with Italian architecture through the medium of Kahn. One only need think of the design project experience of Mario Botta, who inherited from Kahn certain research themes during his collaboration on the Palazzo dei Congressi project in Venice.

This subject matter has already been given wide treatment by the present author, along with Marco Falsetti, in their book Rome and the Legacy of Louis Kahn (Routledge, London, New York, 2018), which includes contributions from many of the protagonists of the time. Her working hypothesis, therefore, is solidly based on research into how much Kahn imparted to the Roman architectural scene, allowing her to claim that one could, in some ways, refer to a “Kahn season” experienced by all concerned. To go beyond this, to examine how this shared experience could have been drawn from a background of common ideas, is undoubtedly a task beset by uncertainty. However, what is clear and plausible is a recognition of a methodological source and a Kahnian poetic core, founded on a vitally new definition of an architectural organism, in its deepest sense of a design model that reconciles and links together the individual parts of a construction into a single, close relationship based on necessity, and assigns to each of them a common purpose. This interpretation is demonstrable – and is, in fact, demonstrated by Elisabetta Barizza – and links Kahn’s work to a European tradition of teaching and theory that found, in the inter-war years in Italy, not only its most modern and inheritable expression, but also its most convincing practical validation. This is to put forward an explanation that is partial, but that is also the task of any architect filled with enthusiasm for their work, even at the project stage. In today’s cultural climate, where it seems impossible to talk of unity and synthesis, the notion of organism remains one of the basic ideas on which one can establish a critical interpretation of constructed reality and, thus, of architectural design itself.

For this reason, then, a return to a study of Louis Kahn is a useful decision: to rediscover to what extent his work is valid for contemporary design, in order to resolve the current impasse in architecture, which has been stalled for decades in abstract, eye-catching researches, continually innovating without any form of central focal point. A new reading of Kahn’s concept of organism, by revisiting his works and his writings, I am convinced, can help our discipline of architecture find its way back to reality. This concept, updated and vital, does not, as his work demonstrates, imply any form of mechanical determinism, but is the expression of the multiple connections that link together elements, systems and structures, which together contribute to the final constructive outcome of architecture. The organism and organicity that Barizza identifies in Kahn’s work is altogether different from the naturalistic arguments utilised throughout history, nor do they have anything in common with the numerous interpretations proffered incessantly from the 16th century up to the current ideas of the organic, which have indirectly traversed modern architecture. The idea used here is more similar to the modern term, unknown before the Enlightenment, of “organisation”, in the sense of a set of rules that govern the coordination of separate elements with one another. This term entered the scientific vocabulary with the meaning of “ordering, arranging” in the mid-17th century, used to indicate a set of parts that collaborate together for the same function. Kahn’s employment of this idea – and his acknowledgement of the importance of necessity, congruence and proportion in design – enables one, in an exemplary fashion, to regard an architectural work as an artificial product of a unifying thought process that does not rely on the study of nature nor even on the study of single works created by architects, but on a form of universal formative structures that operate throughout history, within all histories. All of which goes to say that it is far removed from current thinking – which proves, to my mind, its greater usefulness.