SEMINARIO

Rigenerare il borgo antico del “Castello” di Canosa di Puglia

13 maggio , h 9.15

la rigenerazione del centro antico di canosa

SEMINARIO

Rigenerare il borgo antico del “Castello” di Canosa di Puglia

13 maggio , h 9.15

la rigenerazione del centro antico di canosa

La lezione riguarderà una sintetica presentazione del metodo morfologico processuale come strumento di lettura critica della realtà costruita in divenire. Questa lettura è basata sulle nozioni di “formatività”, capacità di dare forma attraverso un processo dinamico di trasformazioni e “generatività” capacità di generare con un numero finito di regole, un numero potenzialmente infinito di forme. Verranno fatti alcuni esempi di lettura riguardanti il palazzo italiano e alcuni esempi di progetto derivato dalla lettura inteso come ultima fase di trasformazioni in atto.

Politecnico di Bari – Dipartimento dICAR

Corso di Laboratorio di Progettazione Urbana II

Prof. Matteo Ieva

arch. Nicola Scardigno, arch. Anna Linnik, arch. Giuseppe Volpe

2020-2021

Esistono oggi scuole di morfologia urbana? La tradizione italiana è stata rivolta, almeno in parte, all’uso operativo degli studi sulla forma urbana. Ma è ancora possibile proporre, oggi, ricerche in chiave progettuale e didattica, oltre che interpretativa? Qual è il lascito “aggiornato” dei maestri che hanno contribuito alla nascita di una scuola di morfologia urbana?

manifesto giornata di studio 14 gennaio 2021 (1)

Nello sforzo di rinnovare gli strumenti di partecipazione alla costruzione dei numeri della rivista, la redazione di U+D – Urbanform and Design intende organizzare l’issue number 15/2021 sul tema La ricerca di morfologia urbana in Italia. Tradizione e futuro, chiamando a collaborare gli autori fin dalla sua impostazione, che sarà discussa in una Giornata di Studio in programma per il 14 gennaio 2021.

L’iniziativa ha due finalità correlate tra loro.

Si tratta di sperimentare un nuovo metodo di progettare la pubblicazione pensandola come processo e definendone la struttura in forma partecipata.

L’iniziativa ha, poi, lo scopo di contribuire a rilanciare il dibattito sui temi della forma urbana riguardata nei sui esiti tangibili e indagata secondo metodi razionali e trasmissibili. Pur in un’accezione ampia e aperta del termine “morfologia urbana”, l’interesse dell’incontro sarà rivolto alle ricerche basate sullo studio concreto dei fenomeni urbani e sul loro esito progettuale.

Tema importante sarà anche il ruolo fondamentale che scuole e maestri hanno avuto, in Italia, nel costruire un pensiero originale sugli studi urbani, oggetto di una nuova attenzione in campo internazionale. Il dibattito dovrebbe essere incentrato, secondo le intenzioni degli organizzatori, non su uno sguardo storico e retrospettivo, ma sull’attualità del loro lascito che va confrontato con le questioni più urgenti che la crisi della città contemporanea pone.

Proponendo una riflessione rivolta al futuro ma basata sui temi della condizione contemporanea, sembra utile porre, allora, i seguenti interrogativi:

cosa si intenda oggi per morfologia urbana;

come essa venga studiata e proposta nella didattica delle scuole italiane;

come venga studiata e proposta nel progetto di architettura;

quali nuove prospettive di ricerca si possano avanzare per interpretare la fenomenica attuale.

Le differenti posizioni che emergeranno nella giornata di studio, strutturata in forma di tavoli di discussione, contribuiranno a formare un quadro sintetico delle attività teoriche, progettuali e didattiche praticate nelle diverse scuole.

Senza avere la pretesa di esaurire il quadro delle ricerche sul tema in corso in Italia, alla giornata sono invitati studiosi delle sedi in cui sono presenti Corsi di Laurea in Architettura che operano su questo stesso orizzonte di sperimentazione con metodi e fini diversi ma, riteniamo, spesso complementari.

L’evento è aperto all’intera comunità di studiosi e architetti che operano in questo settore e che potranno partecipare come uditori mediante la piattaforma on line.

link: https://meet.google.com/fvb-wjkv-uze

Lettura e Progetto – Nuova serie di Architettura

FRANCOANGELI. MILANO . 2020

di GIUSEPPE STRAPPA

Questo libro di Matteo Ieva, che attendevamo da tempo, è il risultato di un lungo lavoro di analisi e verifica condotto presso il Politecnico di Bari, per molti anni, con la passione, ma anche con l’attenzione critica, dovuta al proprio maestro. E’, sotto molti aspetti, un testo non facile per le tante interpretazioni legate ad ambiti disciplinari che si sovrappongono a quello strettamente morfologico e che aprono nuove prospettive di ricerca. E’ anche un testo poliedrico, che indaga la materia di studio mettendo al centro, di volta in volta, temi che sembravano ormai scontati e che riemergono invece in tutta la loro sorprendete attualità: la nozione di organismo e quella complementare di tipo; il problema della lettura della realtà costruita e la sua coincidenza col progetto; la questione della lingua come uso condiviso di un parlato quotidiano, e di un’ espressione “alta” quale portato dell’edilizia speciale. Temi che aprono, a loro volta, insiemi di problemi complessi. Il lettore avrà modo, leggendo il testo, di apprezzare quanto l’autore abbia affrontato questa materia con competenza e strumenti nuovi.

Vorrei qui accennare a due possibili, complementari chiavi di lettura del suo lavoro.

La prima è di carattere, direi, ontologico. Riguarda la necessità dell’uomo di ordinare il mondo attraverso la forma. Senza mai esplicitarlo direttamente, il testo mette in luce la capacità del metodo caniggiano di indagare la realtà costruita attraverso insiemi finiti, unità che si aggregano e dequantificano mantenendo la propria individualità. Nella lettura come nel progetto, Caniggia ha indagato la capacità di dare un limite alle cose: il senso del confine caniggiano, scrive l’autore, permette di delimitare gli spazi in modo tale che “le parti, in esso correlate, acquisiscano una specifica finitezza proprio attraverso il reciproco rapporto”.

Mi sembra, questo, un aspetto del tutto attuale del testo, proprio perché controcorrente rispetto dibattito contemporaneo sugli strumenti disciplinari. La crisi della nozione di limite ha origine, in realtà, già dai principi formali dell’architettura moderna, tanto alla scala edilizia (la negazione dell’idea di facciata, la ricercata simbiosi tra spazio esterno ed interno ecc.) quanto a quella di organismo urbano (l’idea di crescita per assemblaggi, lo zoning funzionale ecc.). È stata, questa, una delle grandi perdite dell’architettura moderna, le cui conseguenze sono ancora evidenti: senza la nozione di limite non si dà nemmeno quella di organismo, perché la capacità di dare un confine permette di dare forma leggibile alle cose. Noi percepiamo il mondo costruito attraverso i suoi limiti: le superfici, i confini, le soglie, l’aspetto visibile attraverso cui diamo ordine all’ indistinto, lo comprendiamo, ne individuiamo attraverso lo studio la struttura nascosta. La stessa nozione di territorio non avrebbe senso senza di essa, a partire dal mondo antico, perimetrato dal limes, dal vallo che distingue e individua.

Tutta la ricerca progettuale di Caniggia è rivolta all’ urgenza di proporre questo problema e occorre tenerne conto nel seguire le riflessioni di Ieva.

La seconda chiave di lettura che ritengo importante è l’anti-individualismo del pensiero caniggiano: la sottomissione delle pulsioni personali alla legge generale che dà senso alle cose e senza la quale tutto diviene frammento, parte di un insieme di cui si è smarrita l’unità. La grande lezione di Caniggia è stata rivolta a questo sforzo di individuare le regole, profonde e in continuo mutamento, che permettono la lettura ordinata della realtà oltre la percezione individuale, che consentono di leggere concretamente il costruito e progettarlo con una stessa logica sintetica, condivisa e trasmissibile.

Questo spiega, per entrare nel merito diretto di una parte importante dei contenuti del libro, perché i disegni di Caniggia siano così poco accattivanti. L’estrema brevitas, l’assenza di ogni aggettivazione individuale e di qualsiasi indulgenza al dettaglio personale, permette di mettere a nudo un sorprendente rigore, consentendo di scoprire un mondo ancora ignoto agli architetti, dove la forma è l’oggetto condiviso di una scienza nuova e torna ad essere l’aspetto riconoscibile di una struttura anche quando, come nota l’autore, le cose sono molto complesse e il visibile è solo traccia di una verità. L’interesse si rivolge, dunque, alla struttura stessa del costruito (a quello che non vediamo ma conosciamo attraverso lo studio della forma) ai suoi processi formativi, che diventano la sostanza stessa, ineludibile, dell’architettura.

Ogni elemento non necessario diviene, per Caniggia, ostacolo alla comprensione, ogni aggiunta all’essenza delle cose oscura pericolosamente l’evidenza della verità. Questi disegni, che l’autore aveva voluto scarni, essenziali, apparentemente lontani da ogni emozione, finiscono per comunicare invece una sorta fascino iniziatico, una poesia dell’ascesi. Come la regola di un francescano che eliminando religiosamente il superfluo, permette di vedere in ogni cosa la mano di Dio e la sua saggia bellezza.

Credo sia interessante notare come nel proprio lavoro Ieva ricostruisca i progetti caniggiani con lo stesso spirito, con la stessa rigorosa, castigata asciuttezza, con cui il maestro avrebbe rappresentato i suoi progetti nell’età del disegno digitale.

É evidente, nei disegni di Caniggia, il tentativo di ricondurre la complessità del mondo costruito ad unità.

Il che comporta, per chi voglia oggi rappresentare i suoi progetti in modo compiuto, un notevole sforzo interpretativo. Occorre, infatti, seguire il filo rosso dell’insegnamento caniggiano per riempire lacune, disegnare parti appena accennate nei disegni originali, ricostruire facciate mancanti. Con una tecnica computerizzata, peraltro, che non consente approssimazioni o deroghe. E forse, come nella linguistica, il traduttore-interprete, per fare bene il proprio lavoro, deve anche avere una buona dose di credenze logiche e ontologiche affini al parlante.

Il lavoro di Ieva non è stato, dunque, semplicemente la restituzione in 3D di un corpus di disegni di grande valore scientifico e didattico. Si tratta, piuttosto, di un poderoso lavoro ermeneutico, un’opera dimostrativa di “riprogettazione” non molto diversa da quella che il maestro proponeva ai suoi studenti. È stato necessario ripercorrere, secondo il metodo caniggiano, appunto, i processi che hanno generato le forme, riapplicare le leggi di aggregazione degli elementi, la formazione di strutture e sistemi. Quelli qui pubblicati potrebbero essere definiti disegni “complementari” che concludono un processo per certi versi rimasto aperto. Sono, in qualche modo, essi stessi, non solo esegesi del testo, ma, soprattutto, progetti che propongono un modo nuovo di vedere gli esiti concreti del metodo.

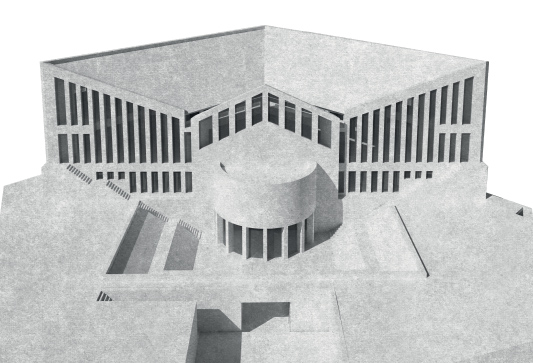

D’altra parte, Caniggia stesso ripeteva che chi volesse continuare la sua ricerca, dovrebbe rinnovarla di continuo, “aggiornala” come diceva, ai tempi che cambiano. Il suo poco conosciuto ultimo progetto per l’ampliamento della Facoltà di Architettura di Roma, a Valle Giulia, pubblicato nelle pagine che seguono, è peraltro un testo non finito, insolito e apparentemente contraddittorio, dove compaiono elementi del tutto inediti quali la pianta triangolare o il pieno in asse proposto in alcune varianti (che non si spiegano, come scrive l’autore, con l’adesione alla forma del suolo e nemmeno con la soluzione di problemi distributivi). Un’eredità enigmatica che sembra non voler lasciare certezze, ma proporre nuovi quesiti.

Credo questo sforzo di restituzione critica del corpus dei disegni caniggiani, dimostri come Ieva sia uno dei rarissimi studiosi che perseguono davvero un rinnovamento del pensiero del maestro attraverso una ricerca originale e, dato fondamentale, non solo teorica. I suoi progetti, che raramente pubblica, secondo una tradizione di riservatezza ereditata dal maestro, hanno apparentemente poco a che fare con la produzione caniggiana, così come Caniggia, peraltro, non ha mai imitato Muratori. È evidente, tuttavia, la presenza di regole comuni, riportate in modo innovativo alle condizioni contemporanee, come un sostrato geologico di principi condivisi che spiegano gli esiti visibili in superficie e danno loro senso. Queste regole producono non solo la struttura profonda degli organismi, ma propiziano una sintesi estetica che pone le questioni della lingua e dei linguaggi, dell’impiego della parole, di un codice condiviso contro l’uso individualistico dell’espressione architettonica. Il che, in un periodo di crisi e di crollo dei codici, come quello che stiamo attraversando, è un problema forse irresolubile. Ma è giusto, ritengo, che si cerchi una strada, si indichi una scelta di campo e di metodo che darà i suoi frutti nel futuro.

Rimane il fatto che la consuetudine dell’autore con il metodo di Caniggia, con i problemi dell’applicazione concreta dei suoi insegnamenti alla luce di contesti nuovi, ha costituito la condizione per scrivere un testo che certamente rappresenta un passo in avanti nella conoscenza di una scuola di pensiero che non ha avuto in Italia buona fortuna, ma che desta crescente interesse all’estero. Proprio per questo mi permetto di suggerire all’autore, per concludere, di considerare la possibilità di un’edizione in lingua inglese della sua opera. Questo consiglio è basato sulla mia esperienza con i corsi di Urban Morphology impartiti in lingua inglese presso l’Università Sapienza di Roma, attraverso i quali mi sono reso conto dell’interesse, e anche della sorpresa, con cui studenti di diversa provenienza culturale si affacciavano a un mondo di studi progettuali basati su principi razionali e trasmissibili, all’idea, per loro nuovissima, di forma come esito di processi in atto. Principi analoghi a quelli che, appunto, Matteo Ieva espone qui con esemplare chiarezza.